Book excerpt: The GM Who Worried Antonio Gates Was a One Year Wonder

- Dominic Mucciacito

- Sep 2, 2025

- 13 min read

The following is an excerpt from "Salty Dogs: The Chargers Unshakable Quarterback Room" by Dominic Mucciacito.

"We're the football team," General Manager A.J.Smith said. "We decide who gets a contract, how much they get and for how long."

September 11, 2005. Fresh off of a surprising berth in the playoffs and suddenly brimming with young talent, the San Diego Chargers needed a touchdown in the final minute if they wanted to win their opener against the Cowboys.

Hall of Fame coach Bill Parcells and his defensive coordinator Mike Zimmer sent another blitz, in an afternoon full of them, hoping that the Chargers' vertically-challenged passer, Drew Brees would either panic, or go down.

Backpedaling Brees stood in the pocket and lofted a 32-yard pass on 4th-and-14 to Eric Parker with a minute left to set up 1st-and-goal from the 7-yard line.

From here the Chargers would normally look for Antonio Gates who set an NFL record for touchdowns (13) by a tight end the previous season with his ability to box out defensive backs and out-jump them.

Brees tried a fade pattern to Keenan McCardell on 1st down. Incomplete. Tight end Justin Peele never separated from the defensive back on 2nd down, so Brees sailed a pass over both of their heads. He tried McCardell again over the middle but the ball was tipped before Keenan was sandwiched, and rag-dolled to bring up 4th down.

At this point the Chargers would have to throw a pass to Gates, right?

On his final pass of the afternoon Brees aimed a pass at Parker, running a slant. As Parker jumped at the goal line to try to catch it cornerback (and present day Jets head coach) Aaron Glenn swatted at the pass from behind; tipping the ball to himself for a game-sealing interception.

So, where was Antonio Gates?

Though perfectly healthy, Gates was watching the game from the Chargers' sideline in a T-shirt; the victim of both his own success and the hubris of his general manager, who had suspended him for three games for . . . not signing the raise he had earned on his timeline.

It was a different time.

Though he had dramatically outperformed the free agent contract he signed as an undrafted prospect, by 2005 Gates and his agent refused to play for the one-year, $380,000 minimum. Even the Chargers agreed that he was more valuable than what they technically owed.

When the negotiations bled into training camp and the long-term deal reflecting his value to the team failed to materialize, the team opted to inject some urgency into the proceedings by threatening Gates with a three game suspension if he didn't report to camp by a fabricated deadline.

"It's disappointing, but it's a business," said the Chargers general manager A.J. Smith.

Though Smith refused to discuss the negotiations in dollars and cents he did clarify that the Chargers would not give Gates a deal equal to that of star Kansas City tight end, Tony Gonzalez; the highest paid tight end.

"That's the position we've taken on that, and we're very comfortable with that," said Smith. "Gonzalez is an eight-year guy, a six-time Pro Bowler, a darn good player, where our guy is caught in the system of exclusive-rights free agency, $380,000, which we've stepped out of the box on. He's had one year of production, he's a one year Pro Bowler, and he's an extremely important part of our team."

"We're comfortable with what we're offering and we're willing to go more. It's not acceptable on the other side," said Smith.

Sure, he's good, and he deserves a raise, but he can't expect to be the highest paid tight end in the NFL. I mean, he might be a one year wonder.

Technically, the same trepidation could have been applied to Smith who had presided over exactly one winning team at that point.

"At the time, you're always trying to figure out, 'Can you do it?'. Anything you do. When you do that it's like 'Okay, I belong here.' After that first touchdown, I was like, 'I am pretty good.'" -Antonio Gates

As crazy as it sounds now, few people criticized Smith at the time. Though no one is an overnight success, Gates’ rise to an All Pro (and eventually the Professional Football Hall of Fame) was about as close as you can get.

The distance between Kent State University and the Pro Football Hall of Fame is only 30.9 miles, if you wanted to make the drive. But tell that to 22-year-old Antonio Gates—who desperately wanted to play professionally, albeit in a different sport.

Two years earlier, on the eve of the 2003 NFL Draft, a handful of scouts attempting to discern whether or not Gates, the Golden Flashes' All-Conference basketball player had the tools to play professional football gathered inside the Kent State Field House.

As scouts from the 49ers, Colts, and Steelers and the tight ends coaches from the Browns and the Chargers settled in the power forward completed his stretching.

What happened next did not send them scurrying to the pay phones to call their front offices in a flop sweat. Though, truth be told, they all probably had cell phones by then.

The power forward, regarded as a "tweener" by the NBA, labored through some agility drills, ran a few listless routes, and appeared to be carrying some extra padding on his 6'4", 260-pound frame. A 4.8 second time in the 40-yard dash could have been the nail in the coffin of his athletic career.

At the suggestion of then Chargers' tight ends coach, Tim Brewster, they ended the workout early. With his last semester in college coming to an end, Gates had just failed another eyeball test.

"It is important that people know you walk among them without fear."

The team that employed Brewster was not in a position of leverage, having lost seven of its final nine games to finish 8-8, missing the playoffs for the seventh straight season. The front office was starting another rebuild, the latest in a line so long that the fans didn't bother to count anymore.

Bereft of talent and chemistry, the Chargers decided to cut ties with two aging veterans who had played for them in its lone Super Bowl. Junior Seau and Rodney Harrison left the organization a year after the architect of that AFC Championship squad, general manager Bobby Beathard.

The Spanos family had placed high hopes on a new general manager who had helped guide the Bills to four straight Super Bowls in the nineties who was almost immediately diagnosed with cancer and died.

Fifteen days away from picking 15th in the NFL draft, John Butler died after a battle with lung cancer. He was 56.

The Chargers turned to his longtime assistant who had followed him from Buffalo to run the team. Albert J. Smith, who everyone knew as A.J., had worked for the Spanos family before, serving as a director of pro scouting briefly in 1986.

When the time came for the Chargers to pick—for Smith to make his very first pick as an NFL GM—he punted; trading down to the bottom of the first round to select cornerback Sammy Davis Jr.. In Smith's defense Frank Sinatra refused to test at the combine.

Eventually Smith's eye for talent would help resurrect the franchise and build a championship-caliber roster that won the AFC West division five times in six years. Unfortunately his over-developed ego cut both ways. "It is important that people know you walk among them without fear." read a quote attributed to Abraham Lincoln on a placard on Smith's desk.

He famously played "chicken" with NFL royalty; drafting Eli Manning, despite the family's threat to sit out a year, eventually fleecing the New York Giants for multiple first round picks, plus a third-round pick, and a fifth-round pick the following year.

He also let his relationship with head coach, Marty Schottenheimer, deteriorate to the point of avoidance and silence treatment. When asked to categorize his working relationship with Smith, Schottenheimer said, "There is, and has been, no relationship. In the last couple of years, there has been very little, if any, dialogue."

Schottenheimer was fired after going 14-2 in 2006. Brees, the franchise quarterback with an injured shoulder, was low-balled after playing on the franchise tag in 2005. Brees signed with the New Orleans Saints in the spring and, even though he claims his right arm is incapable of throwing a football in 2025, in between he did okay in the Big Easy.

Can you name another Hall of Fame quarterback under the age of thirty who was allowed to walk as a free agent for zero compensation? Me neither.

Smith, who passed away in 2024 after a bout with prostate cancer at the age of 75, was fired in 2012 after missing the playoffs for the third straight year. Though his winning percentage is the best in Chargers history, his teams flamed out in the playoffs which led to critics nicknaming him "The Lord of No Rings."

Between Smith's hardened mishandling of his relationships with Brees and Schottenheimer, and his overrated draft performances that eventually caught up with the team, it’s no wonder that such a talent-laden team missed its opportunity to win a Super Bowl.

Egomaniacal, tenacious, obstinate, Smith's greatest strengths were also his professional undoing.

A two sport star at Central High School in Detroit, Gates had accepted a football scholarship from Nick Saban to attend Michigan State. The biggest selling point was that Saban initially agreed to let him play basketball for Tom Izzo after football season ended.

It is hard to imagine two bigger titans in coaching—at the same school! Gates figured that someone should pinch him because he might have been dreaming.

But sitting out his freshman football season as a Prop 48 qualifier was not his dream scenario. His grades fell. Then Saban tried to move him to defensive end. Then linebacker.

When Saban reneged on the basketball agreement thinking that two sports would bury his academics Gates decided to transfer. He never played one down of college football.

"Now, when I look back on it, and his reasoning for doing and saying things that were true, not true, whatever, but my mind (then) was that I couldn't comprehend all that," Gates told ESPN in 2010.

"Playing basketball, football and school. It would've been difficult. So now I'm able to see it, but at 16 years old—I was just turning 17—it was difficult for me to understand that after he told me I could play basketball. And that was my love."

Though it had already opened doors for him, football was still just a means to an end. You don't spend every waking moment practicing your jump shot to just give up when someone tells you no.

"That was the reality of it. I was in love with basketball."

He transferred to Eastern Michigan University where he played part of a season before transferring to the College of the Sequoias, a junior college in California, to focus on his academics. Eventually, Gates transferred to Kent State University in northeastern Ohio where he played power forward for the Golden Flashes.

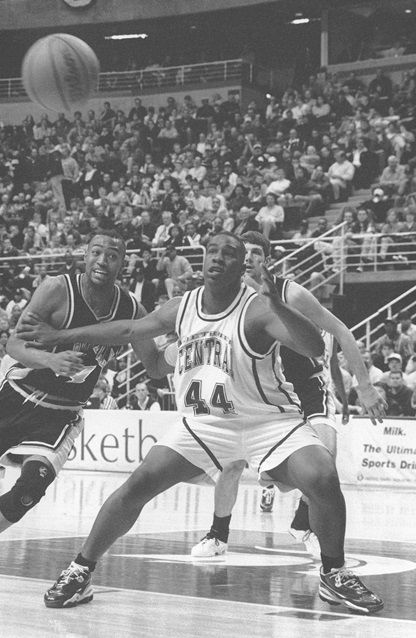

Kent State enjoyed its best season in 2001–02. The Golden Flashes set MAC records for overall wins (30), conference wins (17), and rode a 15 game winning streak into the NCAA tournament.

Seeded tenth in their bracket, Kent State beat its first opponent, the seventh-seeded Oklahoma State Cowboys. Next the Flashes toppled second-seeded SEC champion Alabama 71–58 to advance to the Sweet Sixteen. A 78–73 overtime win over third-seeded Pitt made Kent State the first MAC team to advance to the Elite Eight since 1964.

In his first NCAA tournament against the best basketball players in the country, Gates wasn't just holding his own, he was making a name for himself. Why wouldn't you start dreaming about playing in the NBA?

Still, Gates kept hearing from his coaches that NFL scouts mindful of his previous football potential, were attending Kent State games to check him out.

"I look up and random NFL teams are at a basketball game. I'm averaging 20 points so I'm like, I know you all know I'm going to the NBA. They talked to me after the games to see if I was thinking about playing football," said Gates.

Gates gave the football scouts his best stiff arm.

"I'm not going to be a part of something when I'm the main piece over here. It didn't really make sense to me. Then I became a senior and they (scouts) still was coming."

But by the end of his senior year he realized there wasn't much of a future in the NBA for 6'4" power forwards.

The story has been told in alternating versions, but it is the intervention of others that led to Gates signing a two-year contract with the San Diego Chargers as an undrafted free agent.

Rob Murphy, now the head basketball coach at Eastern Michigan, was a Kent State assistant who lobbied scouts to take a harder look.

Chargers coach Marty Schottenheimer's brother Kurt, who was the Lions defensive coordinator was also an early advocate.

Tim Brewster, the Chargers tight ends coach at Gates' workout, cherry-picked—to borrow a basketball term—the raw potential he had already seen him showcase in his report to the Chargers front office. "If I had been truthful to the organization about what I saw that day we probably wouldn't have signed Antonio." said Brewster.

Years later Gates would credit Brewster for giving him the inside track to signing with the Chargers.

“I had dealt with guys coming out of high school who weren’t honest with me, and I was looking for a genuine guy,” said Gates. “Tim worked me out, but I wasn’t promised this or that. In fact, he told me I might be on the practice team or I might get cut. He was realistic with me.”

This same realism meant coming to terms with letting go of his favorite sport.

“I sat down with close friends of mine, and we talked about how I had to stick with football,” Gates said. “I had to put everything I accomplished in basketball behind me.”

Though Brewster was honest with Gates, he wasn't as candid with his peers representing other NFL teams. So as the other scouts filed out, Brewster held back, hoping nobody else knew that Gates had sprained his right ankle a week earlier playing in the Portsmouth Invitational; a college hoops exhibition for NBA scouts. (Anecdotally, in some retelling of this story it was his hamstring. Who can say?)

A.J. Smith had just taken over the job and needed to be convinced that a high school football player could make the leap without playing in college.

The cost? San Diego gave a $7,000 signing bonus to Gates, who in two years went from all-conference power forward to All-Pro. Both seasons cost the Chargers an annual salary of $225 thousand.

The prototypical "freakishly athletic tight end" or rather, the exception (seeing as there were so few of them) had been established by Kansas City's Tony Gonzalez; a two sport star at Cal Berkley who was gifted with a broad frame, quick feet, baffling body control for someone that size, reliable hands and virtuoso's feel for how to use them all.

Playing college basketball had uniquely prepared Gates to create separation from defenders. A standard basketball court measures 94 feet long and 50 feet wide—not much space for big people to lose track of one another. On a football field 360 feet long and 160 feet wide it would be virtually impossible for one person to stay with him. Even those that could would have to content with Gates' leaping ability to win the rep.

On the court Gates was accustomed to rebounding against players several inches taller. His skill for cutting off of screens became angles for receiving passes. Too short to play in the NBA, he now towered over defensive backs.

Wearing the number 43, Gates, the undrafted free agent dove into the Chargers playbook. What he lacked in experience, he more than compensated for with talent.

"It became clear real fast that he was going to make the team," said the late Marty Schottenheimer of Gates' first summer. "You can't find that type of athleticism in men his size."

The coaching staff began to see the scout's vision; the rest of the league would get a look next.

His production spiked from 24 catches and two touchdowns as a rookie to 81 receptions and 13 touchdowns (the latter is an NFL record for tight ends) in 2004.

In one game Gates found two defenders hovering around him on a play in which his assignment was pass blocking. It isn't hyperbole to say that he changed the game.

Every team wanted to find another wide-framed, Ferrari on a pogo stick. The next Antonio Gates. Basketball players he knew kept calling him to ask Gates if he thought they too could make it in the NFL.

As an undrafted free agent, he had played his first two seasons for the minimum salary.

While the Chargers recognized Gates had outperformed his contract, they were hesitant to offer a salary comparable to more established players like Tony Gonzalez, given Gates had only one elite season.

Despite missing Smith's deadline, Gates signed a six-year, $22.5 million contract on August 23, 2005. Ever the autocrat, Smith placed Gates on the Roster Exempt List, causing him to miss the final two exhibition games and the regular-season opener against Dallas.

According to Gates, he never intended to miss the deadline; telling reporters that he was unable to get a flight back to San Diego the day that they agreed to the Chargers' offer. When reporters tried to clarify that the team could get around the self-imposed discipline with a simple plea to the commissioner, Smith scoffed.

“If there’s some development here that you all are reporting, and there is a hearing and the commissioner says he (Gates) can come back to the San Diego Chargers for Dallas, I think that would be unbelievable,” Smith told beat reporters during a preseason news conference.

“That’s exciting. But you guys are way ahead of me on that.”

If you knew Smith, you can virtually hear the condescension in his voice reading that.

Smith was never going to openly regret sending the letter.

"Absolutely not," he said. "I'm trying to do what's in the best interest for the Chargers. I knew the consequences of the letter. We took a hit, too. We're out our tight end."

"It was crazy," said Gates. "I thought I was prepared for it but I wasn't. I wanted to help the team. It was one of those things I had no control over. I was helpless."

Who knows what sliding doors events ensue had the Chargers not suspended Antonio Gates. Would Smith have been forced to trade Philip Rivers? Would the 14-2 team still stumble out of the playoff gate? Would Spanos choose Schottenheimer over A.J. Smith with a different outcome?

After signing his new deal (becoming the second highest paid TE in the NFL) Gates had 89 catches, 1,101 yards and 10 touchdowns despite being suspended by Smith. The Chargers went 9-7 and narrowly missed the playoffs.

In 2017, Gates caught his 112th touchdown to break the record previously held by same guy A.J. Smith said Gates didn't measure up to: Tony Gonzalez. Last month he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Not bad for a guy who never played a single snap of college football.

Great post